Infant feeding difficulties are some of the most common causes of referrals to general paediatrics. At RHCYP, general paediatricians and dieticians work closely together in the management of infants with feeding difficulties. For dietetic issues, the Paediatric Dietetic page on RefHelp has lots of information about referrals to their service, as well as useful resources and advice for specific dietary issues. Of note, all infants started on a cow’s milk free diet should be supported by a dietitian.

Assessing feeding difficulties in primary care

C.W. & C.H. 19-09-23

Assessment prior to referral

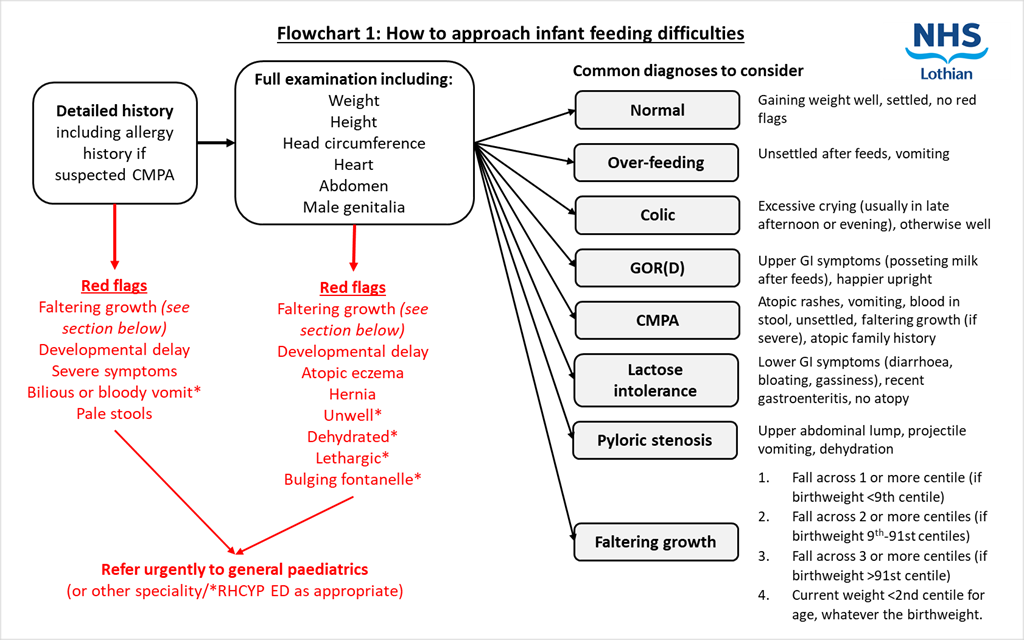

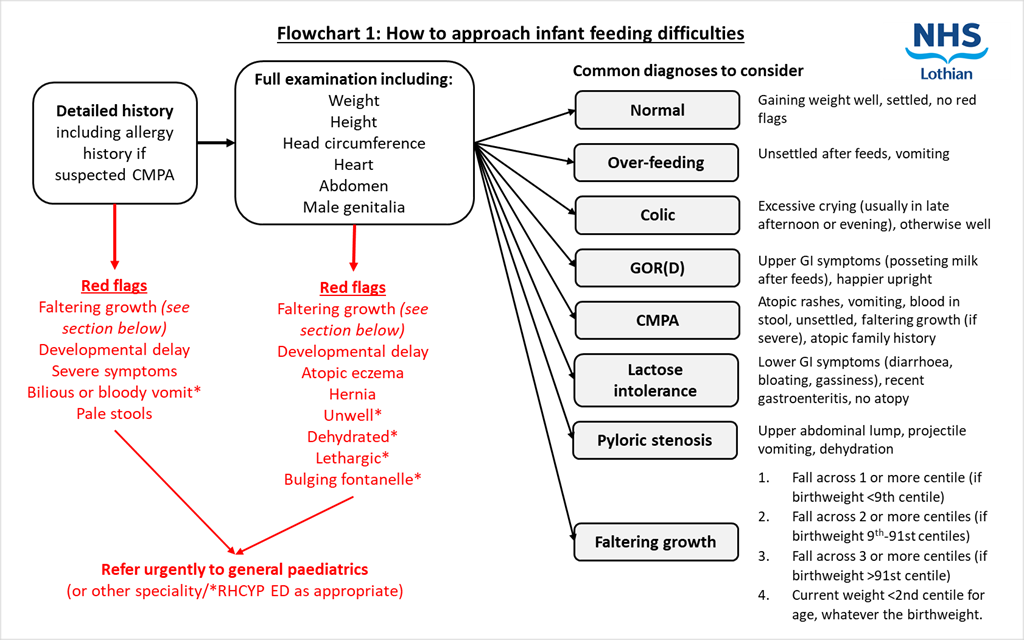

- Thorough history:

- Onset and length of issues (vomiting, crying)

- Birth history

- General health of the infant, including growth

- Allergy/atopic symptoms

- Maternal dietary exclusions

- Nature of stools

- Previously trialled interventions including OTC meds

- Any red flag symptoms/signs

- Plot weight, length and head circumference and examine trend

- Full examination including the mouth, heart, abdomen, skin, and male genitalia

- Apart from a thorough history and examination, no specific tests are required in primary care for feeding difficulties in infants. Most cases are best managed in a test and treat manner – i.e. commencing on treatment to confirm or disprove a diagnosis. Blood tests are rarely indicated.

Who to refer:

- Red flags that warrant an acute assessment by the GP or RHCYP ED

- Unwell child

- Swollen or tender abdomen

- Vomit that is bilious or bloody

- High temperature with vomiting

- Acute onset change in behaviour or new onset vomiting

- Signs of dehydration

- Very distressed or drowsy

- Refusing to feed

- Bulging fontanelle

- Significant blood in stool

- Red flags that warrant urgent referral to specialist care for further investigation and/or management

- Faltering growth

- Severe atopic eczema

- Pale stools

- Suspected severe CMPA

- Suspected mild-moderate CMPA but no clear improvement on cow’s milk elimination diet

- Suspected GOR whose symptoms are not adequately controlled despite appropriate, stepwise primary care interventions

- Developmental delay

Advice only referrals are also welcomed for feeding difficulties. Please refer as usual via SCI Gateway and include “Advice only” in the title.

Triaging

Infants will be seen either in a general paediatric clinic or in the joint feeding clinic which will include an assessment by both a paediatrician and paediatric dietician at the same appointment. This decision will be made at the point of triage.

Occasionally after triaging we may feel that the referral is best managed by dietetics and an appointment will be made with them instead. For further information about referring directly to paediatric dietetics, please see their RefHelp pages.

Who not to refer:

- Infants with suspected reflux who have not tried a step-wise approach in primary care.

- Infants with suspected mild-moderate non-IgE CMPA after commencing a cow’s milk free diet: Please continue on a cow’s milk free diet and refer to Paediatric Dietetics.

- Weaning advice: Please refer to health visitor.

How to refer:

SCI Gateway > RHCYP > General Medicine > LI Basic Sign Referral

Who can refer:

- GPs / Nurse practitioners can refer to general paediatrics or dietetics.

- Health visitors can refer to dietetics directly

Assessment prior to referral

- Thorough history:

- Onset and length of issues (vomiting, crying)

- Birth history

- General health of the infant, including growth

- Allergy/atopic symptoms

- Maternal dietary exclusions

- Nature of stools

- Previously trialled interventions including OTC meds

- Any red flag symptoms/signs

- Plot weight, length and head circumference and examine trend

- Full examination including the mouth, heart, abdomen, skin, and male genitalia

Apart from a thorough history and examination, no specific tests are required in primary care for feeding difficulties in infants. Most cases are best managed in a test and treat manner – i.e. commencing on treatment to confirm or disprove a diagnosis. Blood tests are rarely indicated.

What is normal?

Crying

All babies cry, and some cry more than others. Common causes for crying include hunger, dirty or wet nappies, tiredness, wanting a cuddle, wind, or being too hot or cold. Learning an infant’s cues can help to minimise crying. Infants tend to cry most in their first 3 months of life and on average, infants cry for around 2 hours a day. Infants who cry excessively regularly, particularly in the evening, and are otherwise healthy may have colic (this is not a medical diagnosis but is a commonly used term and does not mean the infant is in pain). An infant who is crying constantly and cannot be consoled which is unusual for them, or if it does not sound like their normal cry, may be ill and should be assessed.

Vomiting

There are many causes of vomiting in infants. It is normal for babies to vomit and if the baby is thriving and otherwise well then parents should be reassured. Overfeeding and reflux are common causes of frequent vomiting in infants and can often be managed with simple measures – see below for specific advice. Red flag signs for vomiting include faltering growth, new onset or bilious or bloody vomit, dehydration, fever, lethargy, and developmental delay, and these mandate urgent assessment.

Stools

It is normal for stools to be unformed and liquid consistency. Frequency can range significantly, particularly for breastfed babies from once weekly stool to 10 stools/day. Providing the baby is well, hydrated and growing normally, we would not be concerned about either stool pattern. Stool colour is also very variable – green stools in themselves are not concerning. Mucus is a common finding in infancy and provided growth is normal is not of concern. Pathological stool colours are red (blood), black (blood) or pale and require referral to paediatrics.

Eczema

Atopic eczema is very common in infancy and is usually not food related. Please refer to the extensive dermatology RefHelp guidelines for management of eczema in children and ensure topical treatments are in place prior to any dietary changes.

Specific feeding issues There are many causes of feeding issues in infants. A detailed history and full examination are essential in determining the most likely cause and ruling out concerning pathology.

Over-feeding

Over-feeding is more common in bottle fed infants than breastfed infants. The amount an infant requires to feed varies between individuals however a general rule of thumb is that most infants aged 1 week – 6 months will require around 150ml/kg/day. If an infant is feeding significantly more than this, it may be that they are overfeeding. Over-feeding can make reflux symptoms worse, and symptoms of overfeeding include being unsettled whilst feeding and frequent posseting.

Advice on how to reduce over-feeding includes:

- Not forcing infants to take more milk than they want during a feed

- Little and often feeds

- Learning the signs for when the infant is hungry, instead of wanting a cuddle

- Learning the signs for when the infant is full

Health visitors will have further advice.

Colic

Colic is not a medical diagnosis but is defined as repeatable episodes of excessive and inconsolable crying (at least 3 hours a day, at least 3 days a week, for at least 1 week) in an otherwise healthy infant with no obvious cause. Apart from the excessive crying, there are usually no other symptoms and the infant is growing well. The crying usually starts in the first few weeks of life and resolves around 4-6 months of age. The crying often occurs later in the afternoon or evening and may be associated with knees drawing up or back arching but is not necessarily a sign of abdominal pain. It can cause significant parental stress, anxiety and depression and requires managing with empathy and concern.

Advice on how to manage a baby with colic includes:

- Reassurance (common problem, should resolve by 6 months of age)

- Strategies to soothe a crying infant (holding, rocking, bathing, winding, music/gentle background noise, car journey, something to look at, suckling, massage)

- Ensure adequate parental support (friends, family, health visitor) and encourage rest where possible

- Safety netting advice

- Reinforce the advice to never shake a baby

- OTC simethicone drops (Infacol) – only to be suggested if parents are not coping. There is no evidence for this being effective

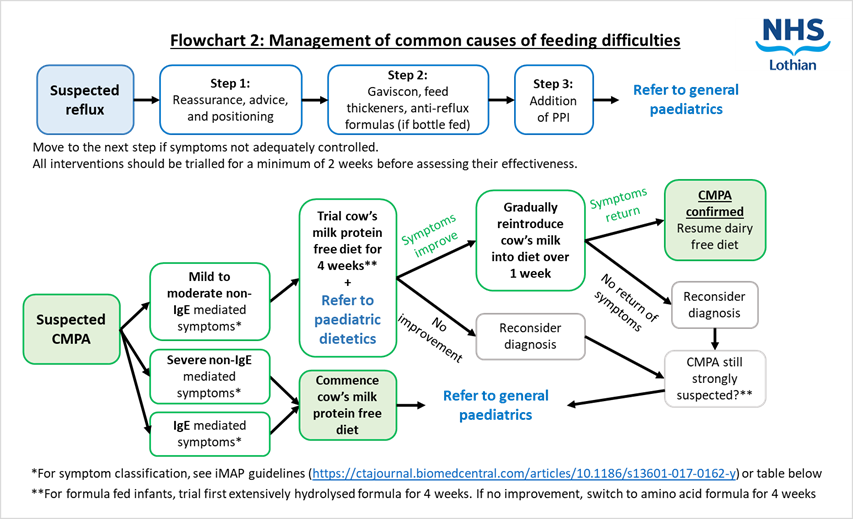

Reflux/GORD

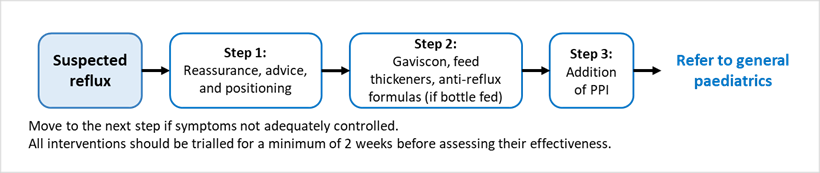

Most babies bring up some milk after feeding – this can be normal. Reflux is physiological and is very common during the first year of life with approximately 2/3rds of infants affected. It improves with age, as the gastro-oesophageal junction matures, the baby spends more time upright and is weaned onto solid food. For most babies who are thriving and undistressed, no treatment is necessary, and it will improve with time. For babies who are not growing well or are very distressed with feeds, treatment is in a stepwise approach, as follows:

If an infant does require treatment for suspected reflux, it is important that all interventions should be trialled for a minimum of 2 weeks before assessing their effectiveness.

First line: Reassurance, advice, and positioning

- Reassure parents that reflux / posseting is common, usually nothing to worry about, and will improve with age

- Advice to reduce symptoms includes

- Burping frequently

- Smaller and more frequent feeds

- Holding the infant upright during and after feeding

- Reducing active play after feeding

Second line: Feed thickeners: Anti-reflux formula, Gaviscon & Carobel

There are several options to try here, and all should ideally be tried before moving onto PPIs. Anti-reflux formulas should not be used with feed thickeners or Infant Gaviscon.

- Anti-reflux formulas: These can be bought OTC for bottle-fed babies

- Infant Gaviscon: This can be prescribed or bought OTC. Gaviscon causes constipation and so should be introduced gradually.

- Carobel: This is a feed thickener and makes milk less likely to reflux back up the oesophagus. It can be bought OTC.

Most of these options are not suitable for solely breastfed babies. Mums can try Gaviscon mixed with a small amount of expressed breast milk. We would not recommend discontinuing breast feeding in order to try the thickened formula. Please consider treatment with PPI earlier.

Third line: PPIs

- Omeprazole: See Formulary East / BNF for dosing. Anti-reflux formulas require stomach acid to promote the thickening process and so PPI may reduce the effectiveness of these – if a thickener is required with a PPI, use Carobel with standard formula.

If there is no improvement with Omeprazole, an infant should then be referred to general paediatrics for further assessment and management. Domperidone may be advised as an option by us but should not be initiated in primary care without discussion with medical paediatrics. Please also note that Ranitidine, previously used in infants with reflux, is no longer available for use in babies or older children.

Cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA)

CMPA is caused by an immune response to the proteins in cow’s milk. These are found in cow’s milk-based formulas and the breast milk of a mother who eats dairy. It is rare under 4 weeks of age. Infants under 6 months of age who have GI symptoms related to dairy are far more likely to have CMPA than lactose intolerance.

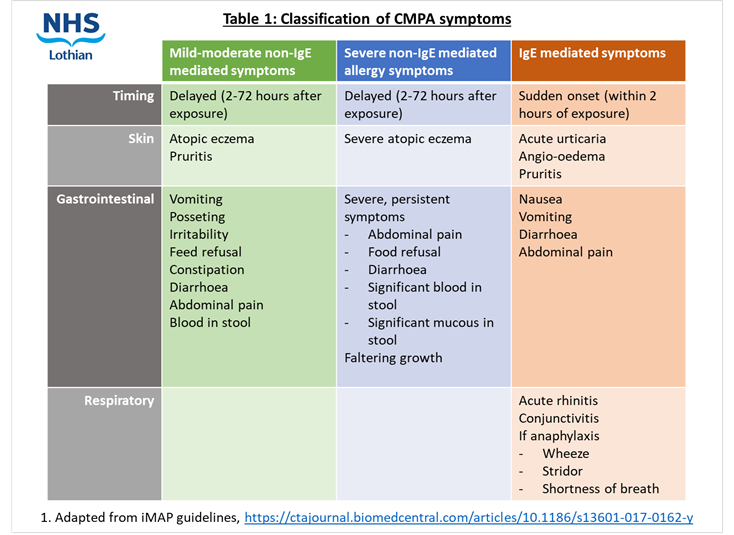

There are two types of reaction:

- IgE mediated, which causes classic immediate hypersensitivity symptoms

- Non-IgE mediated, which produces delayed symptoms. Non-IgE mediated CMPA affects approximately 2% of infants (iMAP guidelines, 2017) and is difficult to accurately diagnose as the symptoms are vague and it has no specific quick diagnostic test – the test for this is a milk challenge.

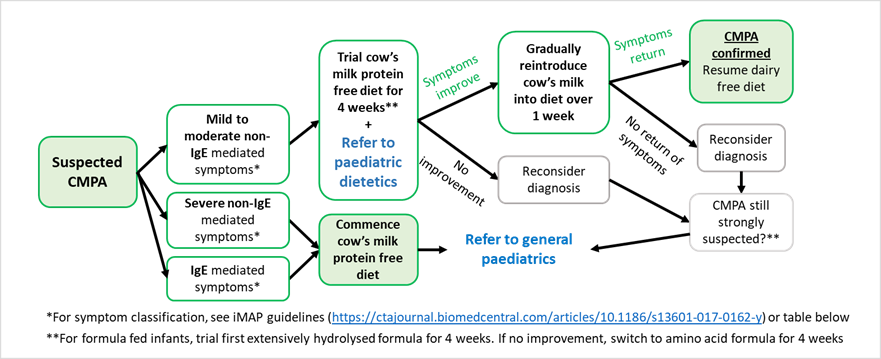

If considering a diagnosis of CMPA in primary care, please refer to iMAP (International Milk Allergy in Primary Care) guidelines. These set out clinical presentations of CMPA and guidance on which presentations should be referred on and which diet is most appropriate. (https://ctajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13601-017-0162-y, see figures 2 and 3)

To diagnose non IgE mediated CMPA, remove cow’s milk protein from diet (either maternal dietary exclusion if breastfeeding or switching to specialist hypoallergenic formula) for a period of 4 weeks. Look for resolution of symptoms. Even with resolution of symptoms, the most important thing to confirm the diagnosis is re-challenge with normal formula or reintroduction of dairy to maternal diet if breastfeeding.

When discussing the trial of a dairy-free diet, breast feeding mothers should be supported to continue breast feeding if this is their wish.

Here is a useful leaflet for parents about how to reintroduce cow’s milk into an infant’s diet: https://apps.nhslothian.scot/refhelp/guidelines/ResourcesLinks/IMAP%20milk%20challenge%20to%20confirm%20CMPA.pdf

A baby has failed the milk challenge if they see a recurrence of symptoms on the reintroduction of milk and thus a diagnosis of non-IgE CMPA can be made. If reintroduction of dairy is successful, then the diagnosis of CMPA is refuted and the baby and mother can continue normal unrestricted diets. A breast-feeding mother’s calcium requirements can be difficult to meet through oral diet alone. If they are going dairy free, even for just 4 weeks during a cow’s milk protein free trial, we would recommend mothers start calcium and vitamin D supplementation. These can be prescribed or bought over the counter and is something that the paediatric dietician will discuss further with the mother at their appointment.

If an infant is formula fed, they should first try hydrolysed formula for 4 weeks. If no improvement of symptoms, then the diagnosis should be reconsidered. If CMPA is still strongly suspected, they should then try amino acid formula as second line for 4 weeks. If no improvement on either formula, an alternative diagnosis should be considered, and the infant should go back on to standard formula.

If a patient is confirmed to have CMPA, they are advised to continue to avoid cow’s milk protein in their diet and to attempt to rechallenge at least 6 months later or from 12 months of age via the support from Paediatric Dietitians. An infant with likely IgE mediated or severe non-IgE mediated CMPA should be referred to General Paediatrics at RHCYP for specialist management. Any infant started on a long-term cow’s milk free diet should also be supported by a dietician.

We would caution against any other food exclusions without discussion with a dietitian. Soya-based formula should not be used as an exclusive feed in infants under 6 months of age.

Specialist formulas: These are formulas prescribed to manage cow’s milk protein allergy and should be prescription only on the NHS. They are expensive, costing up to 5x the price of the standard milk, and cost NHS Lothian approximately £900,000 per year (2018/2019). They can be split into 2 types: extensively hydrolysed formulas or amino acid-based formulas.

Extensively hydrolysed formulas (EHF): The cow’s milk protein fragments are partially broken down. Some of these fragments have the potential to cause an allergic reaction still in some infants. 90% on non-IgE CMPA can be treated successfully with EHF.

Amino acid-based formulas (AAF): The cow’s milk protein fragments have been completely broken down into their comprising amino acids which do not cause an allergic reaction. This is first line for IgE-mediated allergy.

Infants commenced on specialist formulas should be referred to dietetics.

Infants with suspected allergy to food proteins other than cow’s milk (e.g. peanut, egg) should be referred to General Paediatrics for further assessment.

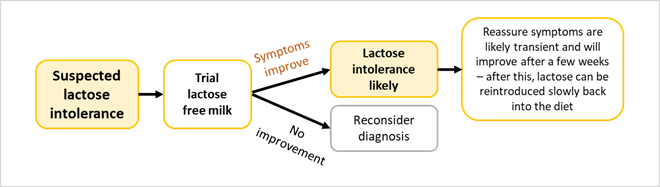

Lactose intolerance

This is not an allergy and is very rare in infants under 1 year of age. In infants it is either secondary or congenital. Secondary lactose intolerance is the most common form, occurring transiently for a few weeks after gastroenteritis or an inflammatory bowel condition.

No special laboratory tests are required. If the baby is bottle-fed, a trial of a lactose-free milk for 6-8 weeks is the best way to test and treat whilst the gut recovers. Lactase drops are not a good alternative. Lactose intolerance is best managed in the community and no referral to paediatric dietetics is needed. Lactose-free formula is available over the counter and similar in price to standard formula and so does not need to be prescribed.

Congenital lactase deficiency is extremely uncommon and presents within a few days of birth with profuse watery stools and dehydration. Urgent referral to paediatrics is necessary.

Pyloric stenosis

This is caused by a progressive stenosis of the pylorus in the stomach. This often presents aged 1-2 months (although can present at up to 5 months of age) with progressive projectile vomiting, vomits of partially digested milk, hunger after vomiting, dehydration, faltering growth, and lethargy. On examination, an abdominal mass may be palpable in the epigastric region. Infants with suspected pyloric stenosis require a same day referral to paediatric surgeons.

Faltering growth

This is not a condition in itself, and instead can be a sign of many conditions including feeding difficulties, acute illness, CMPA, GORD, or a child safe-guarding issue. Faltering growth is classified in infants under 12 months of age as one or more of the following:

- Fall across 1 or more weight centile spaces, if birthweight was below the 9th centile

- Fall across 2 or more weight centile spaces, if birthweight was between the 9th and 91st centiles

- Fall across 3 or more weight centile spaces, if birthweight was above the 91st centile

- Current weight is below the 2nd centile for age, whatever the birthweight.

There are NICE guidelines for recognising, assessing and managing faltering growth in infants (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng75/chapter/Recommendations#faltering-growth-after-the-early-days-of-life)

Faltering Growth is a red flag sign and requires urgent referral to general paediatrics for further investigation. In the majority of cases, there isn’t an underlying medical problem, but it is important to pick up and address faltering growth early.

Refer all infants with faltering growth directly to General Paediatrics.

Whilst waiting for an appointment, please consider:

- Establishing feeding goals and a feeding diary

- Minimum 3 hourly feeds

- Top-ups if a breastfeeding infant (5-10ml/kg/feed)

- Monitor weight closely

For healthcare professionals

A RefTalk video from March 2023 on “Feeding and Growth Issues in Infancy” is available to view on the RefTalks page: RefTalks – RefHelp (nhslothian.scot)

RefHelp page for Paediatric Dietetics

NICE guidance for faltering growth

NHS Lothian Lactose Intolerance

Lactose free diet sheet(V.1 Aug 2019)

NHS Lothian info sheet on CMPA

For parents

Support For Crying And Sleepless Babies | Cry-sis

NHS Lothian Feeding Difficulties leaflet

NHS Lothian Milk Reintroduction leaflet

NHS information on posseting/baby reflux and things you can do to ease symptoms

Unicef information and videos on breastfeeding, bottle feeding and night-time care