This guideline relates to investigating adults with symptomatic or asymptomatic hyponatraemia. It should be emphasised these are guidelines and do not replace clinical judgement. Mild hyponatraemia is common, and patients should be considered on a case-by-case basis and managed in the realms of realistic medicine. The purpose of investigating hyponatraemia is to identify and address the underlying cause in situations of diagnostic uncertainty and detect the minority of patients who may require referral to secondary care or urgent medical admission.

Classification of hyponatraemia:

- Mild >130 mmol/L

- Moderate 125-129 mmol/L

- Severe <125 mmol/L

Signs and symptoms of hyponatraemia

Hyponatraemia is often an incidental finding. Symptoms are usually non-specific and include:

- Cognitive deficit, falls, lethargy, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, headaches, and – in severe rapid onset cases – seizures and coma.

- Chronic hyponatraemia can lead to increased risk of falls, gait disturbance, cognitive deficits and osteoporosis.

Some medications to avoid in the hyponatraemic patient:

- Trimethoprim

- Co-trimoxazole

- Mirtazapine

- Carbamazepine.

Please see Primary Care Management for potential causes and details of initial approaches and investigation.

Who to refer:

When to consider urgent admission:

- Sodium <125 *mmol/L or

- Sodium 125- 129 mmol/L and symptomatic or acute onset (<48 hours**) hyponatraemia

- Hypovolaemia – associated with a disproportionately raised urea compared to creatinine

e.g. D+V – consider the need for admission for IV fluids.

* if sodium <125 mmol/L then urgent follow up in primary care should be arranged if the patient is not being admitted to hospital;

** if the onset of hyponatraemia is unknown then it should be presumed to be chronic hyponatraemia (>48 hours duration) unless there is evidence to the contrary.

- Advanced CKD – please seek urgent renal advice.

Criteria for referral to endocrinology

Referrals will be triaged by endocrinology to either advice only, or an appointment:

- Hyponatraemia where there is suspicion of adrenal insufficiency (patients with hypotension, hyponatraemia or hypoglycaemia should be discussed with the endocrine registrar on call to arrange an early short synacthen test or admission).

- Hyponatraemia in the range of 125-130 mmol/L where there is either:

– concern about symptomatic hyponatraemia or

– diagnostic uncertainty (after initial causes excluded) - Persistent hyponatraemia ≤125 mmol/L despite withdrawing culprit medications and where there is no clear underlying oedematous condition.

Who not to refer:

Patients with any degree of hyponatraemia due to confirmed SIADH, where there is suspicion of underlying malignancy. They do not require referral to endocrinology, unless they meet any of the above criteria. Such patients can be investigated according to clinical concern, in the same manner those presenting with weight loss and suspected malignancy. The likelihood of underlying malignancy is lower in patients with mild, chronic and stable SIADH.

How to refer:

SCI gateway to endocrinology (or appropriate other specialty depending on associated findings).

1.If this is a new finding of hyponatraemia confirm on repeat blood test (where not severe / acute requiring immediate intervention).

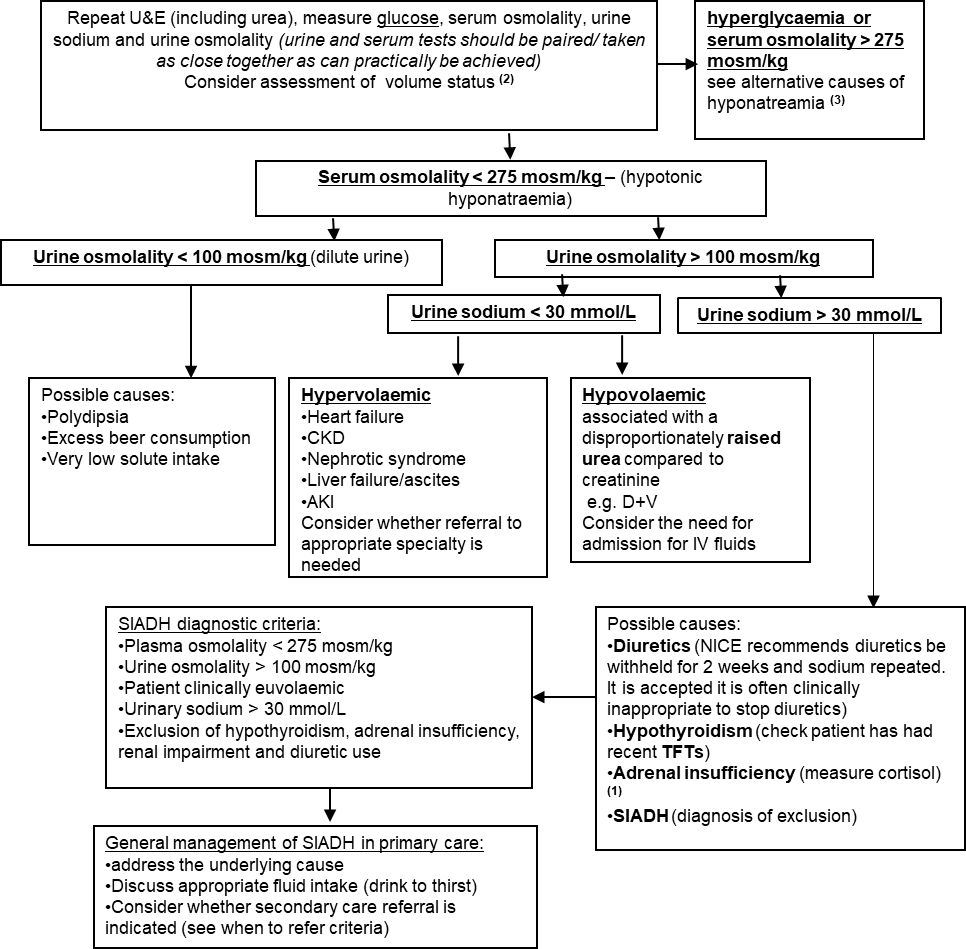

2.Check plasma glucose (hyperglycaemia can cause a hypertonic hyponatraemia and a common cause of ‘not clinically relevant’ hyponatraemia). Hyperglycaemia is one of the commonest causes of hyponatraemia, and overlooking a glucose check can lead to much unnecessary investigation.

3.In most situations the clinical assessment of volume status does not add much. It is mainly useful in identifying patients with volume overload such as in congestive cardiac failure or nephrotic syndrome. Urea is helpful in identifying hypovolaemia: a disproportionally raised urea compared to creatinine suggests dehydration.

4.Advanced CKD – consider seeking specialist advice. High urea increases measured plasma osmolality but freely crosses the cell membrane so doesn’t change the effective osmolality (urea doesn’t cause fluid shifts between the intracellular and extracellular compartment and doesn’t cause hyponatraemia). High urea may cause a normo-osmolar or hyperosmolar hyponatraemia, but these patients are still at risk of symptoms due to cerebral oedema.

5.GPs may wish to check urine and serum osmolality (see Resources and Links) but always important to check for the obvious causes first (and may wish to refer where those are unclear).

6.Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone (SIADH)

This is characterised by hypotonic hyponatraemia, concentrated urine, and a euvolaemic state. Following exclusion of hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, renal impairment and diuretic use, the technical diagnostic criteria are:

- Plasma osmolality < 275 mosm/kg

- Urine osmolality > 100 mosm/kg

- Patient clinically euvolaemic

- Urinary sodium > 30 mmol/L.

Causes of SIADH include:

- Drugs – there are many including NSAIDs, paracetamol, PPIs, ACE inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, opiates, dopamine agonist, some anti-psychotics, carbamazepine, ecstasy. If in doubt check the BNF.

- If medication/drug related – stop offending drug if clinically appropriate and repeat sodium in 2 weeks (or sooner if concern). Discuss with appropriate specialist if medication can’t be stopped e.g. Psychiatry if anti-psychotic implicated. NICE recommends diuretics be withheld for 2 weeks and sodium repeated, as it is accepted it is often clinically inappropriate to stop them completely.

- Malignancy – Consider CXR. If malignancy is suspected referral via urgent suspected cancer pathway is appropriate. The likelihood of underlying malignancy is lower in patients with mild, chronic and stable SIADH. Note: a normal CXR does not exclude a diagnosis of lung cancer. If there is no other cause for SIADH and there are risk factors for, or high suspicion of lung cancer then refer to respiratory for CT chest (https://apps.nhslothian.scot/refhelp/guidelines/lungcancer/).

- Other causes: CNS disorders (tumour, infection, inflammation, trauma), pulmonary – TB, pneumonia, empyema, aspergillosis, trauma, idiopathic.

Management of SIADH is primarily to address the underlying cause – where appropriate discuss appropriate fluid intake (drink to thirst) – and refer when concerns or diagnosis or management unclear.

7. Consider other causes depending on the clinical picture:

- Inter-current illness: in particular chest infections, UTI, GI upset can cause transient hyponatraemia à address the underlying cause and repeat sodium in 2 weeks (sooner based on clinical judgement) to check for resolution.

- Cancers: consider chest XR (especially if a smoker). Manage as you would any other patient with suspicion of malignancy.

- Hypothyroidism: check TFTs

- Medications: stop culprit medications if safe to do so and repeat sodium in 2 weeks (sooner based on clinical judgement):

- Most common drug causes of hyponatraemia include: thiazides, thiazide-like diuretics, SSRIs, antipsychotics, trimethoprim, co-trimoxazole, and carbamazepine (and see SIADH above)

- Less common drug causes include (this list is not exhaustive, if uncertain consult the BNF): loop diuretics (especially in combination with ACE inhibitors or spironolactone), opioids, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-II receptor antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, anticonvulsants (such as sodium valproate, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam), amiodarone, dopamine antagonists (metoclopramide and domperidone), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Excess fluid intake: ask about fluid intake and polyuria. Possible causes include polydipsia, excess beer consumption, very low solute intake. Urine osmolality will be low < 100 mosm/kg (dilute urine)

- Prolonged physical exertion: exercise associated hyponatraemia occurs during or up to 24 hours after prolonged physical activity (e.g. marathon running, backpacking) due to ingestion of large volumes of hypotonic fluids (water or sports drinks) in excess of losses in sweat and urine etc.

- Fluid overloaded states (hypervolaemic): ascites/liver disease, congestive cardiac failure, AKI, nephrotic syndrome à manage underlying disease process and consider referral to appropriate specialty

- Adrenal insufficiency: consider if significant fatigue, hyperpigmentation, hyperkalaemia, postural hypotension or hypoglycaemia. Check early morning cortisol (8- 9am): a random cortisol of >300 nmol/L (in a patient not on glucocorticoid therapy) suggests adrenal insufficiency is very unlikely. Patients suspected of having adrenal insufficiency should be discussed with the endocrine registrar on call to arrange an early short synacthen test or admission.

Pseudohyponatraemia: is an artefactual cause of low measured sodium in the lab. It can be caused by high triglycerides or protein in the blood sample. It is typically associated with a normal plasma osmolality of 275 to 295 mosm/kg. Paraproteins in myeloma can cause a pseudohyponatraemia, so consider serum electrophoresis and urine Bence Jones protein if raised total protein. Consider hypertriglyceridaemia and hyperproteinaemia (and alcohol) in hyponatraemia with normal or high plasma osmolality. Check glucose, total protein and triglycerides.

Systematic approach to investigating hyponatraemia in situations of diagnostic uncertainty where further investigation is felt appropriate.

This flow diagram is intended to be used only where there is a significant hyponatraemia and diagnostic uncertainty. Please ensure the information in the Primary care management section has been followed prior to following the steps below.

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone.pdf

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hyponatraemia

Hyponatraemia Guideline Development Group. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014 Feb 25;170(3):G1-47. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-1020.